Chapter III The sacrificia language¡ªinscriptions

Section I An Overview of Inscriptions on Bronze Wares

In Chinese archaelogy, bronze ware refers to wares made of an alloy of copper and tin used in Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties. There are always inscriptions on them, which is called “J¨©n Wén”—½ðÎÄ in Chinese, literally, inscriptions on metal wares. Being a successor of the inscriptions on oracle bones, it came into being in the Yin Dynasty and developed to its zenith in Western Zhou (1046-771 BC). Its contents ranges from sacrificial and ritual ceremonies, expeditions and merit recording to grants and mandates. Up to now, more than 4,000 bronze wares have been excavated and kept by museums in China.

The dots, strokes and strucure in the inscriptions on bronze ware which contain a strong historical flavor, have been a subject for imitation and copying for calligraphers.

Extensive reading (3)

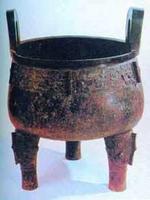

Dayu Tripot Inscriptions on Dayu Tripot

1. Protection of Dayu Tripot: It was made to praise King of Zhou by a man called Yu. The pot is 101.5 cm high, weighs 153.5 kilos. The inscription has 291 characters in 19 lines. It is the biggest tripot made in Western Zhou. It was excavated at Qishanli village of Shanxi Province during the reign of Emperor Daoguan of Qing Dynasty (1821-1850). It was first owned by a gentry called Song Jinjian, and was taked away by the county magestrate Zhou Genglan. In 1850, Song was enrolled into the Imperial Academy and he bought it back with 3,000 tales of silver. Later, Song family declined, the aids and staff of Zuo Zongtang (1812-1885, a minister of the Qing court and a general of the Xiang Army) bought it with 700 tales of silver and presented it to Zuo. In March, 1860, Zuo was impeached, but Pan Zuyin wrote petitions three times to the emperor who finaly pardoned him. To thank Pan, Zuo gave the Dayu Tripot to Pan. Pan was the minister of industry, agriculture, transportation and railways. After he passed away, his brother Zunian took it to their hometown —Suzhou together with another tripot in secrecy. In the later years of the reign of Emperor Guangxu, the Jiangsu Governor of the time Duan Fang who tried every means out to obtain the tripot, but failed. In 1920, an American wanted to buy it from the Pan family with 600 tales of gold and a house and also failed. At the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese War, Pan Dayu, the wife of the grandson of Pan Zuyin, was in charge of the family, she dug deeply in the living room of the second courtyard in two consecutive nights and had the tripot burried. After the Japanese took over Suzhou, they intimated the Pan family hoping to get the tripot, they then searched all over the family and could not find it, they finally looted the house and took away all other properties and collection of relics. After the founding of the People’s Republic, Mme Pan Dayu felt the responsibility of protecting the tripot was too heavy to shoulder, she then denoted it to Shanghai Museum just before its innaugration. The tripot is now housed in the Museum of Chinese History in

|

Beijing. The government awarded Mme Pan with a hefty bonus, but she didn’t even take a penny and led a poor and plain life since. 2. Protection of Guojizibai Basin:

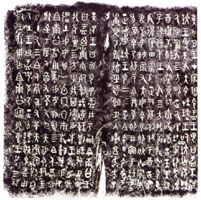

It is a rectanglar basin with handles in the shape of animal heads, 41.3 cm high, 130.2 cm long and 82.7 cm wide and weighs 550 kilos, there is an inscription at the inner bottom with 111 characters as the picture on the right. It was a prize for Guojizibai who won a battle in 815 BC. It was excavated at a county in Baoxi, Shaanxi Province, the Magistrate of that time Xu Fujian took it as his own and sent it to his hometown in Changzhou. During the time of Taiping Uprising, the head of the

|

|

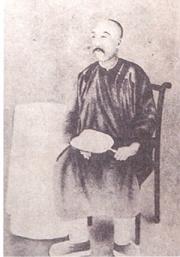

A portrait of Liu Mingchuan

|

Uprising army at Changzhou Chen Kunshu took it over and put it in his residence as a guardian,. Later, Liu Mingchuan, Governor of Zhili,crushed the uprisers with Anhui local army and took Chen’s residence. One night Liu was reading under a lamp and heard a kind of noice that sounded like fighting with swords, he came out of his room and looked for where the sound came. The sound came from a stable, it was the copper rings on a halter of a horse striking on the manger. He then looked at the manger carefully, it was a rare bronze ware with inscriptions on the bottom. Out of sheer surprise and pleasure, he ordered his home servants to have it delivered to his hometown in Anhui where he built a “Basin Pavillion” to house it and never showed it to anybody. Liu (1836-1895) faught against Taiping uprisers in Jiangsu and Zhejiang areas for a long time, he was the first Governor appointed to Taiwan and returned to his hometown in 1891 because of illness. Many high ranking officials of the Qing court coveted this rare treasure, so after Liu’s death, his family hid it away and told others that the pavillion caught on fire and the basin was ruined. At the outbreak of the Anti-Japanese War, the Liu family dug a deep hole outside their house and burried the basin there and planted a small locust tree on top and then the whole family moved to another place to live. The Japanese searched for it in the Liu house several times in vain. During the rule of the nationalist government, the Liu family had to forsake their home again, because the then Anhui Province chairman threatened by force for purpose of getting it, they even dug 3 foot deep in a dozen rooms and failed to find it. Liu Su, the fourth generation of Liu Mingchuan, donated it to the government after Hefei was liberated in 1949. The basin is now housed in Shanghai Museum. Liu Su worked at Anhui Provincial Relics Bureau until he passed away in 1977.

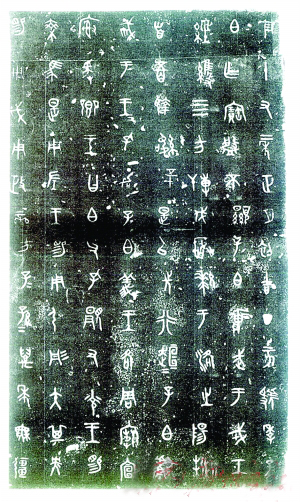

Section II Features and Style of Jin Wen

|

|

We have to look at the features

and style in four phases:

1. Shang period: the inscriptions

were in one, two or ten characters

at most, mostly names of person,

family or tribes. These characters

look simple and dignified. Simuwu

Tripot (on the right) is a respresentative.

2.

Western Zhou period: “Jin Wen”

matured in this period. The start

and finish of strokes were round.

The characters look orderly and

stately. The representative works

are Sanshi Plate (see its inscri-

ptions on the left) and Maogong

Tripot.

|

|

3. Eastern Zhou period: Carved inscriptions appeared at this period. Characters look slim and refined. “Jin Wen” began its decline.

4. Qin, Han and afterwards: As feidal separation ceased in Qin, bronze ware production by kingdoms was stopped. Inscriptions in Qin were only in measuring and weighing units, in Han were casters names and casting time and sized of wares.

Section III The Differences between Jin Wen

and Jia Gu Wen

Due to different tools and material used, Jin Wen is simpler and less picto-graphic. The strokes in Jia Gu Wen are thin and turns are abrupt while as in Jin Wen the strokes are stout and turns are smooth and round.